Kampala’s Daily Monitor reported June 10, 2012, that religious leaders at the annual conference of the Uganda Joint Christian Council called on parliament to move the anti-homosexuality bill forward to prevent “an attack on the Bible and the institution of marriage.” A resolution to that effect was signed by Cyprian Kizito Lwanga, the Roman Catholic Archbishop of Kampala; Jonah Lwanga, Archbishop of Kampala and All Uganda, of the Eastern Orthodox Church of Alexandria; and Henry Luke Orombi, the Anglican Archbishop of Uganda. (According to The Living Church, Orombi earlier opposed the anti-homosexuality legislation. Apparently, he has changed his mind—a change in strategy, no doubt, rather than a change of heart.)

The legislation has received worldwide condemnation by human rights groups and other organizations, including the U.S. State Department. The draconian measure has had an on-again-off-again history, but it once more appears to be under active consideration by a legislative committee. (For the benefit of those who are familiar with the legislation, I will skip an enumeration of its vile provisions. A recent post by Peter Montgomery offers a quick review of the bill and its legislative history.)

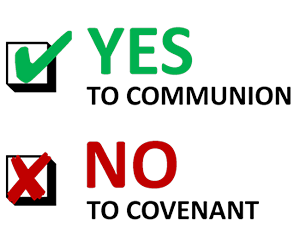

I am calling attention to the declaration by the three archbishops simply to suggest how far apart are the attitudes toward homosexuals within the Church of Uganda and The Episcopal Church. The Ugandan church wants persons who engage in homosexual acts, fail to report suspected homosexuals to the authorities, or even discuss homosexuality openly to be jailed. The Episcopal Church welcomes homosexuals into its churches and, without embarrassment, makes them priests and bishops. Clearly, if both churches were to adopt the Anglican Covenant, each church could raise questions about the other under the agreement, leading to thus far undefined sanctions (“relational consequences”).

In reality, and despite the naïve doctrinal declarations of the Covenant, Ugandan and American Anglicans have very different theological understandings and significantly different cultural presuppositions. Reconciliation, if that is taken to mean that each church comes to approve the position of the other on a subject such as homosexuality, is, anytime soon at least, inconceivable. Honest discussion might lead to reciprocal understanding, but not to approval. Engagement under the terms of Section 4 of the Covenant would be mutually destructive of the principals and of the Communion generally. Contrary to the apparent beliefs (or wishes) of the Archbishop of Canterbury, some problems simply do not have solutions.

There is a silver lining, of sorts, in this situation. Archbishop Orombi has been prominent in GAFCON and was one of the signatories to the GAFCON Primates’ Council’s Oxford Statement of November 2010. That declaration said, in part,

And while we acknowledge that the efforts to heal our brokenness through the introduction of an Anglican Covenant were well intentioned we have come to the conclusion the current text is fatally flawed and so support for this initiative is no longer appropriate.In other words, there is every reason to expect that the Church of Uganda will either never take up the matter of Covenant adoption or, if it does so, will reject the pact. That being the case, it does not matter what The Episcopal Church does with the Covenant, at least with respect to Uganda, as the dispute-resolution procedures of Section 4 will never come into play vis-à-vis the two churches. Five other African primates signed the Oxford Statement as well, so their churches, too, are unlikely to engage with other Anglican churches under the Covenant.

If this is the case, what is the point of the Covenant? The Anglican Communion, having spent untold Christian-hours and dollars (pounds, pesos, etc.) on developing and discussing the document that will soon come before the General Convention, has produced an agreement that is patently unfit for the purpose for which it was intended. To pretend otherwise is delusional.

Uganda is yet another reason for The Episcopal Church to reject the Covenant. The General Convention can justify the time needed to discuss the Covenant only insofar as discussion is needed to discern the most effective and definitive way of saying “no.”

Although there is an argument that in its support of the criminalization of homosexual activity the Church of Uganda is in violation of Lambeth 1998 1.10.d, ". . .while rejecting homosexual practice as incompatible with Scripture, calls on all our people to minister pastorally and sensitively to all irrespective of sexual orientation and to condemn irrational fear of homosexuals . . . ."

ReplyDeleteWouldn't the Covenant provide a structure of accountability, a framework, where the Episcopal Church, say, could call Uganda to the table and ask them to explain their actions to the Communion?

And perhaps such a process--whether or not it led to some immediate change in the attitudes and actions of the Ugandan Church--would send a message to the clergy and people of the Anglican Church of Uganda, which is in so many ways a vibrant and exciting center of Christian life and mission, that their actions are not coherent within the wider Anglican family?

It seems to me anyway that "you go your way, I'll go mine," is a profoundly unbiblical stance within the Christian family. Whether the Covenant as a particular expression is there or not, "mutual responsibility and interdependence" is still and always will be there to wrestle with . . . .

Bruce Robison

Bruce,

DeleteI think talking is fine. The Covenant is not really about talking, however. It does not even require that the “accused” church be heard. The American notion of due process is totally absent from the Covenant.

In any case, I would make a theological case about the wrongness of Orombi’s position without reference to Lambeth I.10 because, contrary to the understanding of some, Lambeth Conference resolutions are nothing more that the declaration of a majority of the attending bishops gathered at a particular time and place. They have no legal or quasi-legal standing within the Anglican Communion.

As for “mutual responsibility and interdependence,” I would refer you to my earlier post “Mutual Responsibility and Interdependence.” The responsibility of The Episcopal Church, as I suggested in that essay, is first to God, which implies an obligation to its members and to the wider society in which it operates. It is not to the Anglican Communion or to the churches thereof. We should, of course, treat other Anglican churches with respect, i.e., not as dependents, but we are not responsible to them or they to us.

Yes, I agree that Lambeth Resolutions have a moral standing, not a legal standing--which is to say, whatever standing they have is rooted in the respect one has for those making the Resolution, the desire one has to be in harmonious relationship with those making the Resolution, and of course the internal persuasive character of the Resolution itself. It's kind of like when your sister asks you to pick up a quart of milk and drop it by her house on your way to work. No legal standing. Similarly, "mutual responsibility and interdependence" is a consequence not of law but of love. If one member suffers, all suffer together; if one member is honored, all rejoice together.

ReplyDeleteBruce Robison