In my last

post on the subject, I offered some objective measures that allow the candidates vying to become Pittsburgh’s next bishop to be compared to one another. Below, I will look mainly at the professional histories of the candidates. There is a little more room for interpretation here, though people of goodwill can disagree both on what our diocese needs and the degree to which the experience of a particular candidate might suggest that he or she is well-equipped to address those needs.

Of course, no one who gets to vote on who will be our next bishop should go to the convention next Saturday without first studying all the material on the candidates on the diocesan

Web site.

The Nomination Committee seems to have selected people with the apparent ability to get disparate groups to work together or to reconcile contending groups. How important are those abilities in our next bishop? We are not of one mind about this. Some people feel we need to put the past behind us and simply move forward without, for example, asking, “What did you do in the church wars, daddy?” Others are concerned that we harbor different understandings of what happened in the Pittsburgh diocese over the past decade and who was responsible for it, differences that may cause or exacerbate future conflict.

On the surface, there is reason for optimism regarding diocesan unity. We have successfully rebuilt our diocese from the ground up. (Joan Gundersen is fond of reminding everyone that, after the 2008 vote to leave The Episcopal Church, the Episcopal Diocese of Pittsburgh owned nothing more than a cell phone.) And we have gotten ourselves to the place where, without embarrassment, we are seeking a new diocesan bishop. Turnout for the recent walkabouts suggested strong interest by laypeople in who that next bishop will be.

On the other hand, the diocese has avoided dealing with the kind of hot-button issues that have divided Christians here and elsewhere, partly because we have been too busy putting the diocese back together. Are we ready to deal with divisive issues when—as they inevitably will—they raise their ugly heads? Walkabout attendance notwithstanding, are we really ready even to be a diocesan community? The failure of Joyful People a year ago is not encouraging. (Joyful People, you may not recall, was a proposed day of workshops and activities for the diocese. It attracted little interest and had to be cancelled.)

Our next bishop will have many tasks on the diocesan plate other than gathering us all into one big happy family: finances, deployment, property management, and litigation among them. Most importantly, a decade from now, we can hope that the Episcopal Diocese of Pittsburgh will be seen as a community that is in the business of diminishing human suffering, not causing it.

With that introduction, let’s take a closer look at the candidates to be our next bishop.

Michael N. Ambler, Jr.

Ambler’s education has taken him to New Jersey, Michigan, and Massachusetts, but one might object that his professional life has been spent exclusively in Maine, where he has been a lawyer and a priest. He is both the youngest candidate and the candidate who has been a priest for the least number of years.

Ambler's pastoral experience has mostly been at

Grace Episcopal Church, Bath, Maine, where he began as priest-in-charge and is now rector. He has been at Grace for 10 years, having first served as an assistant rector at St. David’s, Kennebunk, for about two years. Both parishes have average Sunday attendance (ASA) around 150. Since last year, Ambler has been priest-in-charge of St. Philip’s, Wiscasset, a church with an ASA under 50. He has hired a newly ordained intern with whom he shares responsibilities for the two churches while serving as a mentor to the new priest. This kind of sharing of resources might well be applicable in a diocese such as our own, which includes a number of small, struggling parishes.

Ambler has been an active priest in his diocese. He was a General Convention deputy in 2006 and has served on Maine’s Standing Committee since 2009. He serves as a liaison between the cathedral and the diocese, and he is a member of a task force created by the bishop to examine mission strategy. (There is more useful experience here.) He has served on the diocesan trial court and Province I court, apparently without having to try any cases. Ambler’s legal training would possibly be an asset as our diocese continues to resolve the issues brought about by the departure of Bob Duncan and his followers.

On the reconciliation front, Ambler has had training in conflict mediation from the University of Southern Maine and in mediation and church systems from Lombard Mennonite Peace Center. His

résumé describes his work as a “mediator and consultant” in the diocese of Maine as “frequent and ongoing.” He works with congregations experiencing conflicts of one sort or another and is on a diocesan response team that provides pastoral care in cases of alleged misconduct.

Ambler believes that we will eventually get past our arguments about sexuality by recognizing that standards of behavior necessarily change over time. In fact, he sees a willingness to change as an important characteristic of Anglicanism. Despite his legal background, Ambler does not seem legalistic in his thinking when it comes to the church. (He wouldn’t discipline a priest for offering open communion, for example, even though he is not in favor of open communion and it is not now allowed by the canons.) He believes that both clergy and laypeople should be doing the work of the church outside its doors. (We in this diocese have necessarily been focused on ourselves for the past few years, and this attitude might be one that would be helpful now.)

I have heard a number of people express concern at Ambler’s statement “I believe the stories of the scripture are true.” He went on to say that he does not view them as metaphorical. So, was the world created in seven days? I don’t know that anyone followed up with such a question, but the Ambler declaration seems to demand qualification or explanation.

If you want to see Ambler preach, his Easter 2012 sermon is

here.

Dorsey W. M. McConnell

It is harder to summarize McConnell’s career. He is a decade older than Ambler but has been a priest for 17 more years. The parish where he is currently rector,

Church of the Redeemer, in Chestnut Hill, Massachusetts, is in the Diocese of Massachusetts. Although it has an ASA of only about 175, it has a budget of over $700,000 and, as Episcopal parishes go, a large staff.

McConnell has held other positions in the dioceses of Olympia, New York, and Connecticut. His experience is quite varied. He has, among other things, been chaplain to a New York City trade union, a chaplain at Yale University, has been involved in a ministry to the homeless, and has been part of a shared ministry involving ELCA parishes. He has been a General Convention deputy and alternate deputy, and has been on a Cursillo secretariat. He is on the Commission on Ministry of the Diocese of Massachusetts. Before becoming a priest, he was a polo groom, a wrangler in Argentina, an actor, and a news editor.

Perhaps one of McConnell’s more interesting experiences (and relevant to Pittsburgh) was described by him on our diocesan Web site as follows:

From 1999 to 2002, I helped found and lead the New Commandment Task

Force, a national reconciliation effort within the Episcopal Church,

bringing together laity and clergy, liberal and conservative, to see

themselves and each other as members of the one Body of Christ.

McConnell is also president of Pilgrim Africa, a Christian NGO working in Uganda. I have thought that it might be time for us to enter into a companion diocese relationship. Perhaps McConnell has good connections to help us to find an appropriate diocese in Africa. (I’ve thought that a diocese somewhat out-of-step with its parent church would be a good match for Pittsburgh.)

Readers looking for more details of what McConnell has done over the years should check out his

résumé.

McConnell seems to have Anglo-Catholic leanings but is broadly accepting of different liturgical styles. He appreciates the big-tent that is The Episcopal Church.

Most of the people I have talked to feel that McConnell is one of the more “conservative” candidates, whatever that means. Some people feel that his answers in the walkabouts were carefully couched so as to avoid giving offense. Perhaps, though I certainly wasn’t offended by anything he said.

McConnell’s Easter 2012 sermon (audio only) is available

here.

Scott T. Quinn

I have already said a good deal about Quinn’s candidacy, and I see no need to repeat that here. (See my post “

Musings on the Candidacy of the Rev. Canon Scott Quinn.”)

Quinn has been rector of

Church of the Nativity in Crafton, Pennsylvania, since 1983, the year he became a priest. The weekly attendance at Nativity is only about 80, but the church appears to be healthy, which it was not in 1983. (A sense of the parish can be had in a

Tribune-Review story from September 2008 on the occasion of the hundredth anniversary of the church building.)

While serving at Nativity, Quinn has served stints as a vicar (four years at St. Mark’s, Knoxville) and as a hospice chaplain (two years at Hartland Hospice). He is also serving as chaplain of Old St. Luke’s, which is essentially a wedding chapel.

No doubt, the primary reason Quinn is a candidate at all is that he has been Canon to the Ordinary in our diocese since 2009. Reviews of his efforts have been mixed, but some clergy have found Quinn quite helpful.

Quinn has been active in Boy Scouts, Meals on Wheels, and, improbably, government. He is a councilman in Thornburg Borough.

I could find no sermons of Quinn’s on the Web.

R. Stanley Runnels

Runnels has been rector of

St. Paul’s Episcopal Church in Kansas City, Missouri, since 2006. The church has an ASA over 200 and a multi-person staff, though it has a smaller budget than McConnell’s parish. Before moving to the Diocese of West Missouri, Runnels held three parochial positions in Mississippi. Most recently, he was rector of St. John’s Episcopal Church in Laurel, Mississippi, for 17 years.

Runnels is a three-time General Convention deputy from Mississippi. (He resigned as a deputy to the 2006 General Convention due to his move to Kansas City.) In fact, his involvement in church governance has been extensive. He spent eight years on the Standing Committee of the Diocese of Mississippi. He was president of the Standing Committee for three years and clerk for four. He is currently on the Standing Committee of the Diocese of West Missouri. He has been on committees with responsibility for the constitution and canons of The Episcopal Church and was involved in the rewrite of Title IV. He has served as a consultant on Title IV to several dioceses.

Runnels has been a death-row chaplain, a Cursillo spiritual director, a diocesan ecumenical officer, a trustee of a public school system, a trustee of a Christian day school, rector of another Christian day school, and a soccer coach, among other things.

Runnels tells the story of how he introduced Holy Eucharist into the chapel program of the day school associated with his church. The accomplishment is impressive in that many of the families with children in the school are Roman Catholic. Basically, he set a goal and, very methodically, got all the stakeholders on board. This represents the kind of systematic pursuit of an objective one might expect from someone with the patience to tackle the likes of Title IV revision.

I could find no sermons of Runnels on the Web.

Ruth Woodliff-Stanley

Woodliff-Stanley’s education is interesting in that her non-theological education seems to have contributed substantially to her accomplishments as a priest. She holds an M.S. in Social Work from the Columbia University School of Social Work, and her work experience is not dominated by parish ministry but by various kinds of intervention, facilitation, and consensus building. Like Ambler, she has had training at the Lombard Mennonite Peace Center, in addition to other continuing education in mediation and other matters.

Woodliff-Stanley is now rector of

St. Thomas Episcopal Church in Denver, where she began as priest-in-charge in 2007. This is another rather small church, with an ASA of a bit over 100. (Many Pittsburgh Episcopalians have been surprised that none of our candidates have come from very large churches. It must be said, however, that the typical Episcopal parish—and certainly a typical parish in Pittsburgh—is of modest size.) The Web site of St. Thomas reinforces the impression that Woodliff-Stanley is the most “liberal” candidate. (More on that in a moment.) The parish is described in page headers as diverse, Christ-centered, and committed. There is a page on the St. Thomas Web site intended as a welcome to “GLBTQ persons.”

It is hard to get one’s mind around Woodliff-Stanley’s work record, and, if I am reading her

résumé correctly, I have no idea what she was doing between 1995 and 1998. She held part-time assistant rector positions in Mississippi for about 5 years before and after that period. She also spent four years as director of the Department of Pastoral Care at the Mississippi State Hospital, a mental institution. She supervised the chaplaincy staff, among other duties.

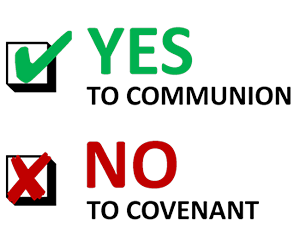

Life seems to have gotten more interesting when Woodliff-Stanley moved to Denver, where she began a private psychotherapy practice in 2002. About the same time, she began consulting for the Diocese of Colorado. Her work with The Episcopal Church in Colorado is perhaps the strongest selling point for Woodliff-Stanley as Bishop of Pittsburgh. The diocese was very divided, and she worked as mediator and facilitator, both part-time and full-time, to bring the diocese together. (The task of maintaining “the highest possible degree of communion” within the diocese sounds like the goal set for the Anglican Covenant. She seems to have developed a better strategy than has the Anglican Communion, however.) Apparently, the work in Colorado has been viewed as very successful, and, if one sees a similar need in Pittsburgh, Woodliff-Stanley might be a good choice as our next bishop.

Woodliff-Stanley continues as a part-time consultant in Colorado and elsewhere. She is also a General Convention deputy in 2012, is on The Episcopal Church Building Fund board, and was on the Commission on Ministry in Mississippi, among other assignments.

I feel it necessary to say something about where the candidates seem to be on the liberal–conservative spectrum. Although Woodliff-Stanley self-identifies as liberal, I suspect that many Pittsburghers feel that more than one of the candidates is more liberal than is this diocese generally. In part, this reflects the fact that Pittsburgh has been something of a reactionary backwater in The Episcopal Church, and any of the candidates from outside the diocese is likely to pull us toward the mainstream and broaden our horizons. What is important in our next bishop, though, is not how liberal or conservative that person is, but whether he or she is accepting of diversity and, despite that diversity, can help us to become a more unified diocesan family. Significantly, each of the three bishops who has helped us since the 2008 schism, including Bishop Price, has been “liberal.” I think that most of us would agree that that has not been a problem or, for that matter, much of an issue.

No one need wonder what Woodliff-Stanley is like as a preacher. (Of course, preaching is not the only—perhaps not even a major—job of a bishop.) Her church’s Web site includes multiple

pages of sermon texts. She also has video of a

stewardship sermon, an

Advent Sermon, and a

Christmas Eve sermon on YouTube.

Postscript

I spent a good deal of time putting this post together, but it hardly seems definitive. I have not even said all I know about the candidates. What is clear, however, is that our diocese has strong candidates from which to choose, something I hope we will do wisely later this week.

First, I eliminated the need to deal with a CAPTCHA, the challenge-response puzzle that sometimes drove people—I include myself here—crazy.

First, I eliminated the need to deal with a CAPTCHA, the challenge-response puzzle that sometimes drove people—I include myself here—crazy.