On April 11, 2012, Mark Harris, on his blog Preludium, published a

comparison of the three General Convention resolutions dealing with the Anglican Covenant that had been submitted to that time. Now there are seven resolutions, and it is time for another comparison. I hope that such an analysis will be helpful, particularly for those who will make a decision next month in Indianapolis about how The Episcopal Church will respond to the challenge of the Covenant.

General Convention resolutions are assigned to a legislative committee, which determines what legislation is sent to one of the two houses for debate. Those related to the Anglican Covenant are being handled by the Committee on World Mission. (All resolutions assigned to this committee, most of which do

not involve the Anglican Covenant, can be found

here.) That the committee has so many topics to consider suggests that it will have limited time to consider Anglican Covenant adoption.

When a legislative committee receives many resolutions on an important topic, it usually holds a public hearing to solicit opinions on the matter in question. It is then free to slice and dice the resolutions before it to fashion one or more resolutions to be considered by bishops and deputies. Of course, either the House of Bishops or House of Deputies can amend the proposed legislation, but the decisions of the committee have great influence.

The seven Covenant resolutions submitted for consideration so far are:

- A126: “Consideration of the Anglican Covenant,” proposed by the Executive Council

- A145, “Continue Dialogue in the Anglican Communion,” proposed by the Executive Council

- B005, “Ongoing Commitment to The Anglican Covenant Process,” proposed by the Rt. Rev. Ian Douglas

- B006, “Affirming the Anglican Covenant,” proposed by the Rt. Rev. John Bauerschmidt

- D006, “Consideration of a Covenant for Communion in Mission,” proposed by Mr. Jack Tull

- D007, “Response to Anglican Covenant,” proposed by the Rev. Canon Susan Russell

- D008, “Affirm Anglican Communion Participation,” proposed by the Rev. Tobias Haller BSG

Resolution A126, the first resolution to be made public—see Episcopal News Service story

here—seems to have had some influence on most of the subsequently submitted resolutions, and especially on Bishop Douglas’s B005, which includes some of the same language. Resolutions A126 and A145, both from the Executive Council, are identical, save for their titles and a single word substitution. I have no explanation for this.

The first Executive Council resolution was proposed before it became clear that Church of England dioceses might block adoption of the Covenant by the English church. B005 was offered after that possibility became apparent but before it was realized. (See

The Living Church story

here.) All the other resolutions appear to have been written after Church of England dioceses rejected the Covenant.

Six of the resolutions can be ranked from most accepting of the Covenant to least accepting:

- B006

- B005

- A126/A145

- D007

- D006

Tobias Haller’s resolution (D008) is something of an outlier, about which I will have more to say below.

To facilitate discussing the resolutions, I have prepared a

chart similar to Harris’s but differing in a number of respects. Because I had to deal with seven, not three, resolutions, displaying parallel columns within this post was not practical. Instead, I created an Excel worksheet, from which I generated the PDF version I have posted on the Web. To facilitate comparison of the provisions of the various resolutions, I assigned them to named categories (“Title,” “Participation in Communion,” “Financial Commitment,” etc.) representing rows in my chart. Finally, rather than displaying the actual resolution text, I paraphrased provisions, both for brevity and to emphasize similarities. I believe that I have represented the resolutions fairly, but I will happily entertain suggestions to improve my paraphrases.

An Overview of the Resolutions

Let me begin by summarizing the various resolutions, using the order shown above, modified slightly for purposes of clarity. I have tried not to editorialize unduly in what follows and not at all in my chart. I have not been so restrained in my closing remarks.

|

| Chart comparing resolutions (page 1) |

B006. The listed backers of this resolution are all

Communion Partner Bishops. Despite the high-sounding

goals of this group, I think it fair to say that its members have been a constant thorn in the side of The Episcopal Church, view the Anglican Communion as more important than The Episcopal Church, and hold a bizarre, minority view of the nature of Episcopal Church polity. Given their past behavior, including submission of a disgraceful

amicus brief in the Fort Worth property litigation, the nature of B006 comes as no surprise.

B006 “affirms” the Covenant and commits to its adoption. Because its backers apparently realize that the agreement is incompatible with current church polity—see the February 15, 2011,

report from the Standing Commission on Constitution and Canons—the resolution would create a special task force to work with the Standing Commission on Constitution and Canons to identify specific changes that would be required to the church’s governing documents and to prepare materials in support of those changes. The resolution requests $20,000 to support this work, with the understanding that a report would be offered to the 78th General Convention, at which formal approval of the Covenant could be effected. B006, in other words, effectively commits the church to adopting the Covenant.

B006 is notable for its repeated use of language lifted directly from the Covenant itself and for its explicit citations of Covenant paragraphs. The resolution makes it clear that Episcopal Church submission to the Covenant should be sincere and complete.

A126/A145. Executive Council proposed A126 last October—see ENS story

here—basing it on the work of the task force called for in resolution

D020 passed by the 2009 General Convention. A126 declares that “The Episcopal Church is unable to adopt the Anglican Covenant in its present form,” which, deliberately, is not a categorical rejection of a covenant in principle. (The Covenant, of course, makes no provision for acceptance short of unconditional adoption, the actions of certain other churches notwithstanding.) A126 commits to continued participation in the Anglican Communion and, more significantly, commits to “dialogue with the several provinces when adopting innovations that may be seen as threatening to the unity of the Communion.” One can read this as merely placating Covenant advocates or as abdicating our church’s authority. It is not clear what this might mean in practice. As noted above, A145 is virtually identical to A126.

B005. Bishop of Connecticut Ian Douglas proposed this resolution. Douglas has a long history of involvement with Episcopal Church governance and with Anglican Communion bodies. He is currently a member of the Anglican Consultative Council and the Standing Committee. He is no stranger to Anglican disputes and has shown no special interest in throwing The Episcopal Church under the bus to achieve Anglican unity. He co-chaired the special commission that considered how the 2006 General Convention should respond to the Windsor Report—the commission’s report is

here, and my own response to the report is

here—and he served as an expert witness supporting the church and diocese in the Virginia property litigation.

B005 largely repeats the language of resolution A126, with two exceptions. First, instead of declaring that the church is unable to adopt the Covenant as presented, B005 would, as a sign of good faith, have us declare that the General Convention “embraces the affirmations and commitments” of the Covenant, minus the controversial Section 4. Second, it would create a body to “monitor the ongoing development of The Anglican Covenant,” particularly with respect to Section 4, to consider constitutional and canonical changes required to adopt the Covenant and what they might mean to Episcopal Church identity, and to consider other matters relating to Anglican Communion unity.

B005 aims to take The Episcopal Church farther down the road to Covenant adoption than does A126/A145. Like A126/A145, however, the ultimate consequences of B005 adoption are unclear. The resolution can be seen as an effort to buy time, perhaps as the Covenant collapses under its own weight, or to advance the church toward adoption at some future time when serious opposition to the Covenant has been neutralized. In his Explanation—since the Explanation for a resolution is not technically part of the resolution itself, I have not included information from the Explanation sections in my chart—Douglas indicates that the resolution is meant to send the signal that The Episcopal Church is “still in the process of adoption,” thereby allowing its representatives to participate in the disciplinary procedures of Section 4. If we believe that the Section 4 procedures are fundamentally misguided, however, as I believe most Episcopalians do, it is not clear why we want to be complicit in carrying them out.

D007. Resolution D007 is a very slightly modified version of the

model resolution proposed by the

No Anglican Covenant Coalition. The proposer is the Rev. Canon Susan Russell, a Coalition member. In addition to the required two endorsers, the resolution lists 11 sponsors from various dioceses,

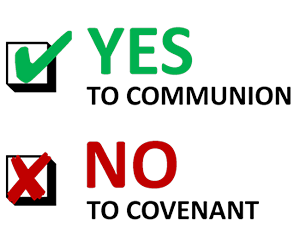

Not surprisingly, D007 rejects the Covenant—“decline to adopt” is the phrase used. While affirming commitment to the Anglican Communion, the resolution clearly asserts what is seen as the proper nature of that Communion. D007 also calls upon church leaders at all levels to seek opportunities to “strengthen and restore relationships” within the Communion.

D007, in its Explanation, attempts to show how we got to where we are now. Specifically, it suggests that anger of what The Episcopal Church has done over the years—ordaining women and homosexuals, consecrating partnered homosexuals, etc.—is what is really behind the Covenant. “Declining to adopt the proposed Anglican Communion Covenant,” the Explanation asserts, “not only avoids permanent, institutionalized division, it opens the way for new opportunities to build relationships across differences through bonds of affection, by participation in the common mission of the gospel, and by consultation without coercion or intimidation.”

D006. This resolution was proposed by layperson Jack Tull in the Diocese of Florida. Tull believes that we should expend no more resources on the Anglican Covenant. As do many Episcopalians, he believes that “A Covenant for Communion in Mission,” which was developed by the Inter-Anglican Standing Commission on Mission and Evangelism (IASCOME), makes a better Anglican covenant than the one our church is being asked to adopt. (Tull included “A Covenant for Communion in Mission” as an

attachment to his resolution.)

D006, like most of the resolutions, commits to continued participation in the Anglican Communion. It also commits the church to “A Covenant for Communion in Mission.” That covenant abjures doctrinal minutiae and focuses on what one might call Christian mission, “promoting God’s presence and healing to those in our world that are broken and disenfranchised,” as B006 expresses it. As for the Covenant, B006 simply declares that the “77th General Convention declines to adopt” it. The resolution goes one step further, however, resolving that the church should expend no additional resources “on this proposed covenant.”

D006 is short on Anglican niceties (or Anglican fudge). It is straightforward, says a clear “no” to the Covenant, and slams the door on the “Windsor Process,” “Covenant reception,” or whatever games Rowan Williams wants to play in his attempt to get all his church’s children to play nice with one another. One has to admire that.

D008. Finally, there is this resolution from the Rev. Tobias Haller BSG, which seems not to be about the Covenant at all, not until one reads its Explanation, at any rate. Haller believes that, since the Covenant has no chance of being widely adopted, it is effectively dead. (I am less sanguine about the Covenant’s longevity, but I understand where he’s coming from.) He therefore wants The Episcopal Church to support something positive to bring Communion churches together.

D008 says nice thing about the Anglican Communion and the Archbishop of Canterbury, says absolutely nothing about the Anglican Covenant, and calls upon church leaders to strengthen relationships in various ways among Anglican churches. In particular, Haller singles out the

Continuing Indaba and Mutual Listening project.

I don’t believe that Haller expects D008 to be adopted without a provision in some resolution being approved that actually addresses Covenant adoption. For the General Convention to simply ignore the Covenant could rightly be seen as passive-aggressive.

A Comparison of Provisions

Having done a quick vertical tour of the columns of my chart, I will now look at the rows, comparing related provisions in the resolutions.

Titles. No two resolutions have the same title. A126 and D007 carry nondescript titles simply indicating that the resolution is responding to the Communion request to act on the Covenant. It is unclear why A145 has a title different from that of A126, but “Continue Dialogue in the Anglican Communion” more properly characterizes the content of the two resolutions from the Executive Council. All the other titles do a reasonable job of suggesting what they are about (for example, B006’s “Affirming the Anglican Covenant”).

Thanks. General Convention resolutions often begin by thanking someone for something. The thanks may be sincere, but one suspects that they are about as often ironic. A126/A145 and B005 each expresses “profound gratitude to those who so faithfully worked at producing the Anglican Covenant.” I suspect there is more sincerity in the latter resolution than in A126/A145. B006 expands this same wording by characterizing the Covenant produced by its authors as expressing “mutual responsibility and interdependence in the Body of Christ,” quoting the

statement from the Toronto Anglican Congress of 1963. (The original meaning of this phrase has been repeated and, I suspect, deliberately, misinterpreted. See my post “

Mutual Responsibility and Interdependence.”) No one is thanked in D006; I suspect that Tull is not especially grateful. D007 offers thanks, though it isn’t clear to whom (“all who have worked to increase understanding and strengthen relationships among the churches of the Anglican Communion”). This, of course, is tasty Anglican fudge. It is doubtful that Rowan Williams is meant to be included among those being thanked in D007, whereas D008, as something of a retirement gift, praises Rowan’s “tireless efforts” on behalf of Communion unity.

Communion Membership. (Note that I am not completely confident about distinguishing this category from the next one.) B006 reaffirms “constituent membership in the Anglican Communion,” which seems innocent enough, but it goes on to cite the Preamble of the church’s constitution, echoing a distinctively conservative view of the Preamble. (See “

Changes Needed in the Constitution and Canons of The Episcopal Church.”) D007 also takes an opportunity to advance a particular understanding of the Communion, asserting that it is “properly drawn together by bonds of affection, by participation in the common mission of the gospel, and by consultation without coercion or intimidation.” The resolution is declaring the kind of Communion to which it is pledging its allegiance. D008 takes a similar approach, referring to “the fellowship of the world-wide Anglican Communion, which is rooted in our shared worship and held together by bonds of affection and our common appeal to Scripture, tradition and reason.” Perhaps an ideal resolution would incorporate ideas from all three resolutions, and particularly those of D007 and D008.

Participation in Communion. A126/A145 and B005 make virtually the same unremarkable commitment to participate in Communion councils and to continue dialogue with other churches. (Actually, the clauses of A126 and B005 are identical. A145 uses “insure” where the others use “ensure.” I don’t see any real difference here.) D006 begins with the same wording, but, whereas the other resolutions say that engagement is for “the continued integrity of the Anglican Communion,” D006 identifies the purpose as “working together for common mission to bring God’s word to all people and to help those afflicted by poverty, hunger, disease and other disasters,” arguably a higher purpose. D007, on the other hand, reaffirms commitment to the Communion, characterized as a “fellowship of autonomous national and regional churches,” again asserting a particular view of what the Anglican Communion should be. B006 likewise asserts a commitment to a particular view of the Communion, namely one in which The Episcopal Church recommits “itself to living in a Communion of Churches with autonomy and accountability (Anglican Covenant 3.1.2), by acknowledging our interdependent life (3.2) and seeking a shared mind with other Churches (3.2.4),” again relying on phrases drawn directly from the Covenant.

Other Communion Commitments. D006 declares a commitment to “A Covenant for Communion in Mission.”

Self-restraint. A126/A145, and B005, using identical language, commit the church to “dialogue with the several provinces when adopting innovations which may be seen as threatening to the unity of the Communion.” One has to ask if this isn’t giving away the store by restraining autonomy, although, technically, these resolutions do not actually require The Episcopal Church to

take any advice it gets. In any case, it is not clear what this would look like in practice or how compliance with the commitment could be assured.

Action on Covenant. A126 and A145 assert that “The Episcopal Church is unable to adopt the Anglican Covenant in its present form,” thereby leaving the door open to adopting a covenant in a different form. D006, which seeks to make the Covenant forever go away, says more definitively that the General Convention “declines to adopt” the Covenant. D007 uses similar wording. It softens the blow by speaking of the church’s prayerful consideration of the Covenant, and it offers specific reasons for rejection, namely believing the “agreement to be contrary to Anglican ecclesiology and tradition and to the best interests of the Anglican Communion.” B005, to demonstrate our dedication to Communion unity, has the General Convention embracing “the affirmations and commitments” of the Covenant, minus Section 4. Of course, although almost everyone admits that Section 4 of the Covenant is its most problematic section, many dispute the glib assertion that the remainder of the Covenant is perfectly acceptable. It looks good only by virtue of Section 4’s being so abysmally bad. B006 “affirms” the Covenant and commits to its adoption “in order to live more fully into the ecclesial communion and interdependence with [which?] is foundational to the Churches of the Anglican Communion (4.1.1),” quoting the Covenant, as this resolution is wont to do.

Autonomy. B006, again using words from the Covenant, asserts that the “mutual commitment” the church takes on via B006 “does not represent submission to any external ecclesiastical jurisdiction (4.1.3) and can only be entered into according to the procedures of The Episcopal Church’s own Constitution and Canons (4.1.6; cf.4.1.4).” Of course, the Covenant’s assertion that it does not restrict provincial autonomy is intended to be reassuring, even though it is transparently false.

Other Covenant-related Action. Two resolutions, B005 and B006, call for the creation of groups that will consider the Covenent further. D006, on the other hand, declares that the church is “unwilling to continue expending funds, time and energy on this proposed covenant.” The stated justification for this position is perhaps weaker than it might be. D006 asserts that the church “is unable to reach a clear consensus” on the Covenant. I suggest that the Covenant is predominately viewed in a negative light by Episcopalians, though many have qualms about the consequences of rejecting it outright.

B006 would have the Presiding Bishop and the President of the House of Deputies appoint a task force to work with the Standing Commission on Constitution and Canons to identify changes to the church’s polity needed “to make the Covenant constitutionally and canonically active and affective.” (The commission has already identified areas of concern, of course.) B006 also calls for the development of materials in support of the necessary changes.

B005 is less clear as to what the Covenant end-game looks like for The Episcopal Church. It, too, has the Presiding Bishop and the President of the House of Deputies appointing a group to further consider the Covenant. In this case, a task force of Executive Council is to consult with the Standing Commission on Constitution and Canons, at least one church historian, and the church’s representatives to the Anglican Consultative Council, which, coincidentally, includes the proposer of this resolution, Ian Douglas. The tasks assigned to this group include monitoring Covenant development (whatever that means), with particular attention given to the controversial Section 4. Like B006, B005 has its appointed body considering polity changes required to support Covenant adoption. The B005 group would also look at consequences for Episcopal Church identity and “consider other such matters helpful to The Episcopal Church’s continued unity with the other churches of the Anglican Communion.

Follow-up to Other Covenant-related Action. Both B005 and B006 have their appointed bodies completing their work for the next General Convention. Whereas the task force called for in B006 reports directly to the 78th General Convention, B005 calls for the work to first be presented to the Executive Council.

Financial Commitment. Only B006 requests funds for its implementation, in this case, $20,000. D006 includes the provision that

no additional funds are to be spent “on this proposed covenant.”

Other Episcopal Church Action. D007 calls on church leaders at every level “to seek opportunities to reach out to strengthen and restore relationships between this church and sister churches of the Communion.” The main provision of D008 falls under this category. It, too, calls for action by church leaders. Since its provisions are not clearly formatted, I will reproduce them here in a more digestible form. Leaders are asked (1) “to find ways to maintain and reinforce strong links across the world-wide Anglican Communion and to deepen The Episcopal Church’s involvement with the existing Communion ministries and networks (especially the Continuing Indaba and Mutual Listening Process);” (2) “to publicize and promote this work within the dioceses of the Church in order to broaden understanding of, and enthusiasm for, the Anglican Communion; and” (3) “to encourage a wider understanding of, and support for, the next meetings of the Anglican Consultative Council and Lambeth Conference.

Parting Thoughts

All of the resolutions are supportive of the Anglican Communion. B006 and D007 are notable for advancing their visions of what the Communion should be, and those visions are remarkably different from one another.

In reality, The Episcopal Church has only limited ability to determine the nature of the Communion. That our church provides such a large fraction of the funds needed to support the administrative structure of the Communion, however, does give us leverage that could be used in the future. Certainly, if our church finds itself having reduced influence in the Communion for its failure to embrace the Anglican Covenant, we must consider whether we can justify continued financial support of the Communion at the same level as in the past.

My sense of the church is that an overwhelming majority of Episcopalians want to reject the Covenant outright and never hear of it again. I think only fear prevents many from advocating that course of action—fear of losing our place at the table; fear of losing our Anglican franchise; fear of a dividing Communion; fear of criticism from those whose Anglicanism is, to us, hardly recognizable. Fear is a poor motivation for action where courage and a prophetic voice are called for.

The Anglican Communion is important for its relationships, those involving churches, dioceses, parishes, and even individuals. The so-called Instruments of Communion are proving themselves to be not instruments of unity but of disunity. Particularly in an age of easy travel and communication, the centralizing tendencies exhibited by the Anglican Communion in recent years are not advancing the gospel. Instead, they are weakening the relationships that truly matter and providing a playing field for those whose goal is the accumulation of power to execute their strategies.

In deciding on whether to adopt the Anglican Covenant or not, The Episcopal Church is pointing the way toward one or another Anglican future. Will we endorse the gospel mission of evangelism and concern for human suffering, or will we put “church” ahead of people and play the power games so characteristic of our sinful race? I cannot but think of the hymn that we, rather unfortunately, banned from our current hymnal that begins: “Once to every man and nation/Comes the moment to decide,/In the strife of truth with falsehood,/For the good or evil side.” That may seem rather melodramatic, but I do think our decision next month is an extremely important one. I fear that it may not receive the attention it deserves because we will be distracted by issues of budget and church organization.

Returning to the resolutions themselves, I personally am happy only with D006 and D007. It is hard to view D008 as a standalone statement of the church. One could imagine combining provisions of these three resolutions to create a strong view of what our church wishes to stand for and the kind of Communion that can justify our participation.

Resolution B006 is, I think, a nonstarter, though it will clearly have its supporters in Indianapolis. Its embrace of the Covenant, would, I think, cause our church to be under siege by the reactionary elements of the Communion for the foreseeable future and would, eventually, result in the demise of The Episcopal Church.

A126/A145 and B005 have the flavor of Anglican fudge and a faint odor of surrender. B005 seems to send us down a road we do not want to travel and suggests that most of the Covenant text is acceptable, which many believe it is not. A126/A145, while seeming to reject the Covenant, agree, in principle, that we have an obligation to consult with the rest of the Communion before we may do what we think good and proper for our church in this time and place. All three resolutions suggest that a modified version of the Covenant presently on offer might be acceptable to The Episcopal Church. I can only ask for how many decades we are willing to expend our energies, money, and enthusiasm on the enterprise of creating such a version.

It is my hope, then, that the Committee on World Mission will focus its attention on D006, D007, and D008. It is time for The Episcopal Church not only to act on its beliefs, but also to stop behaving as though, in our heart of hearts, we feel guilty for doing so. We should be acting boldly for Christ and not be ashamed of the gospel as we understand it.

Update, 7/5/2012. One other resolution on the Anglican Covenant has been submitted and is being considered by the Word Mission Legislative Committee.

D046, from Tobias Haller and Albert Mollegen, declares Covenant adoption moot because other churches have rejected it. This resolution will not fly as it is, but the subcommittee working on resolutions may make use of it.

Update, 7/7/2012. Resolution

C115 has been submitted, which simply kicks the can down the road and does nothing else. It is all of three lines.

Pittsburgh Episcopalians have just received a letter from Bishop-elect Dorsey McConnell in their inboxes. The subject of the missive is how he intends to deal with same-sex blessings in the Episcopal Diocese of Pittsburgh assuming that, as expected, the General Convention approves trial liturgy for such blessings. (The Commonwealth of Pennsylvania recognizes neither civil partnerships nor same-sex marriage, so Pittsburgh priests won’t be performing any same-sex marriages in any case.)

Pittsburgh Episcopalians have just received a letter from Bishop-elect Dorsey McConnell in their inboxes. The subject of the missive is how he intends to deal with same-sex blessings in the Episcopal Diocese of Pittsburgh assuming that, as expected, the General Convention approves trial liturgy for such blessings. (The Commonwealth of Pennsylvania recognizes neither civil partnerships nor same-sex marriage, so Pittsburgh priests won’t be performing any same-sex marriages in any case.)